Violence is a public health crisis.

GUN VIOLENCE PREVENTION:

a public health approach

^^Presentation in partnership with the NAACP; public health models that have been effective at reducing shootings and homicides in other cities, and how we may work to implement them in Massachusetts^^^

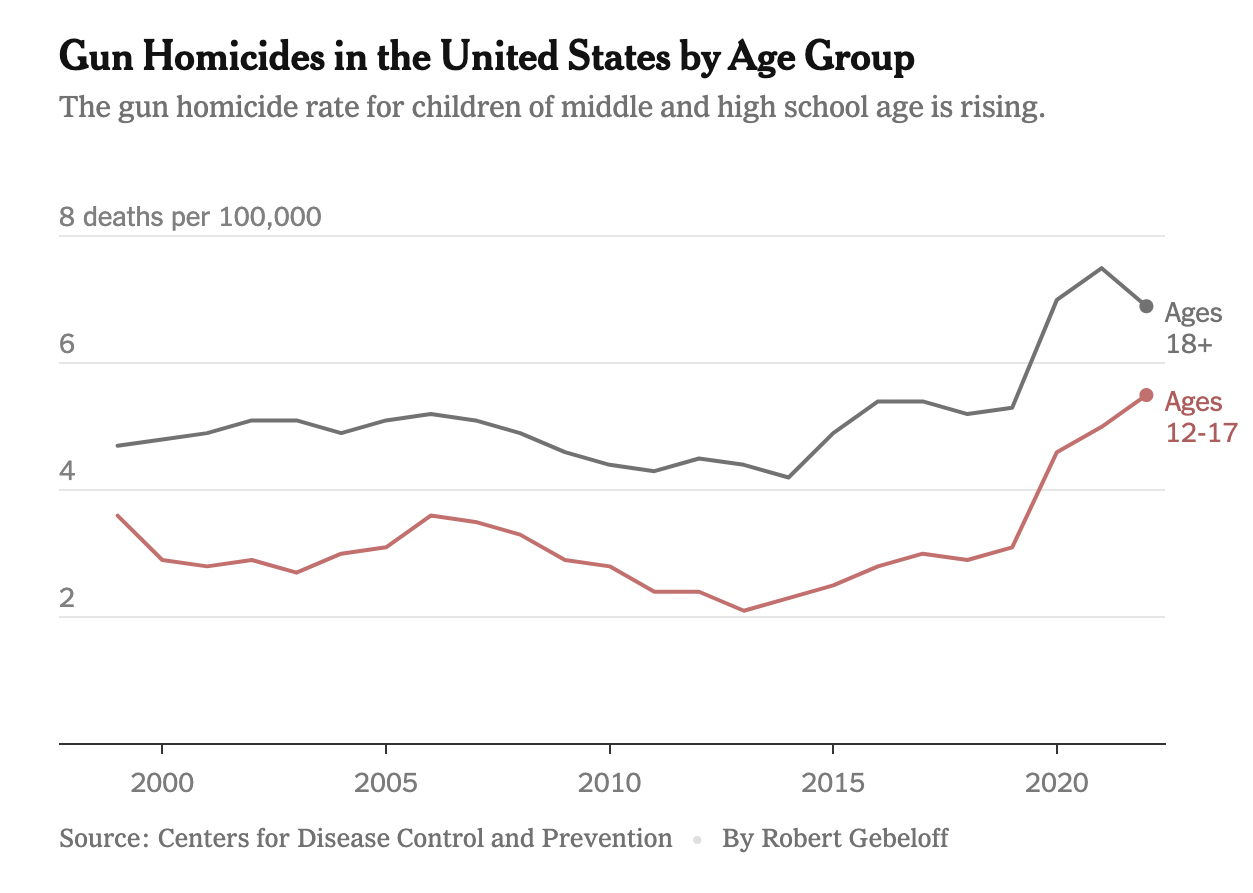

Gun violence is the leading cause of death for Americans under age 19.

For young black men, not only is it the leading cause of death—

it’s higher than the next nine causes of death combined.

DEATH BY FIREARM:

54% suicide

43% homicide

>1% mass shootings

Black children and teens are 14 times more likely to

be murdered with a firearm than white children and teens.

Since 1966, 1,135 persons have been killed in mass shootings. Over that same period, there have been almost a million firearm homicides in total.

(Bleeding Out, Abt)

Nearly eight out of ten homicides

Firearm Homicide Rates for Males by Age/Race

Communities disproportionately affected

by poverty and systemic inequality

suffer the heaviest loss of life due to

rising gun violence.

“There’s pressure to do the right thing and still

somehow be accepted by your peers who hold your life

on their waist. We’re fighting uphill battles and it’s steep.”

COST.

The cost of one homicide to a city is around $10 million dollars cumulatively.

That $10 million comes from:

medical expenses, criminal costs, incarceration, lost wages over time, devalued property, avoidance, economic decline. (Bleeding Out, Abt, p. 23)

The Berkshire County House of Correction budgets for around $90,000/inmate/year. That’s more expensive than Williams College.

Plus the unquantifiable cost of human tragedy, grief, and loss.

Comparatively, the cost of prevention is miniscule.

And it means putting money back into parts of the community that have been disproportionately harmed,

For every dollar invested in violence prevention, cities can save up to $19 in reduced healthcare, criminal, and legal costs.

Gun Violence Prevention Models

^^click above for PRESENTATION on a public health approach to gun violence prevention models^^

Violence clusters.

Violence concentrates among a small group of people in a few places. Interventions should be focused accordingly.

“We must recognize three fundamental truths about urban violence: that it is sticky, concentrating among small numbers of people, places, and behaviors; that it responds to both positive and negative incentives; and that it is closely related to the legitimacy of the state.” ~Thomas Abt

In Boston, less than 2% of the youth population are involved in gangs—yet they are involved in 74% OF THE SHOOTINGS on only 5% of Boston’s street corners.

In Oakland, CA, 400 individuals–just 0.1% of Oakland’s total population–were at the highest risk of engaging in serious violence at any given time.

Referrals to READI Chicago are at extremely high risk of involvement in gun violence. Of the 2,014 men in this analysis, 35% had been shot at least once; on average they have been arrested at least 17 times. READI Chicago serves men who are 1,030%—over 10 times—more likely to be shot and killed than their neighbors.

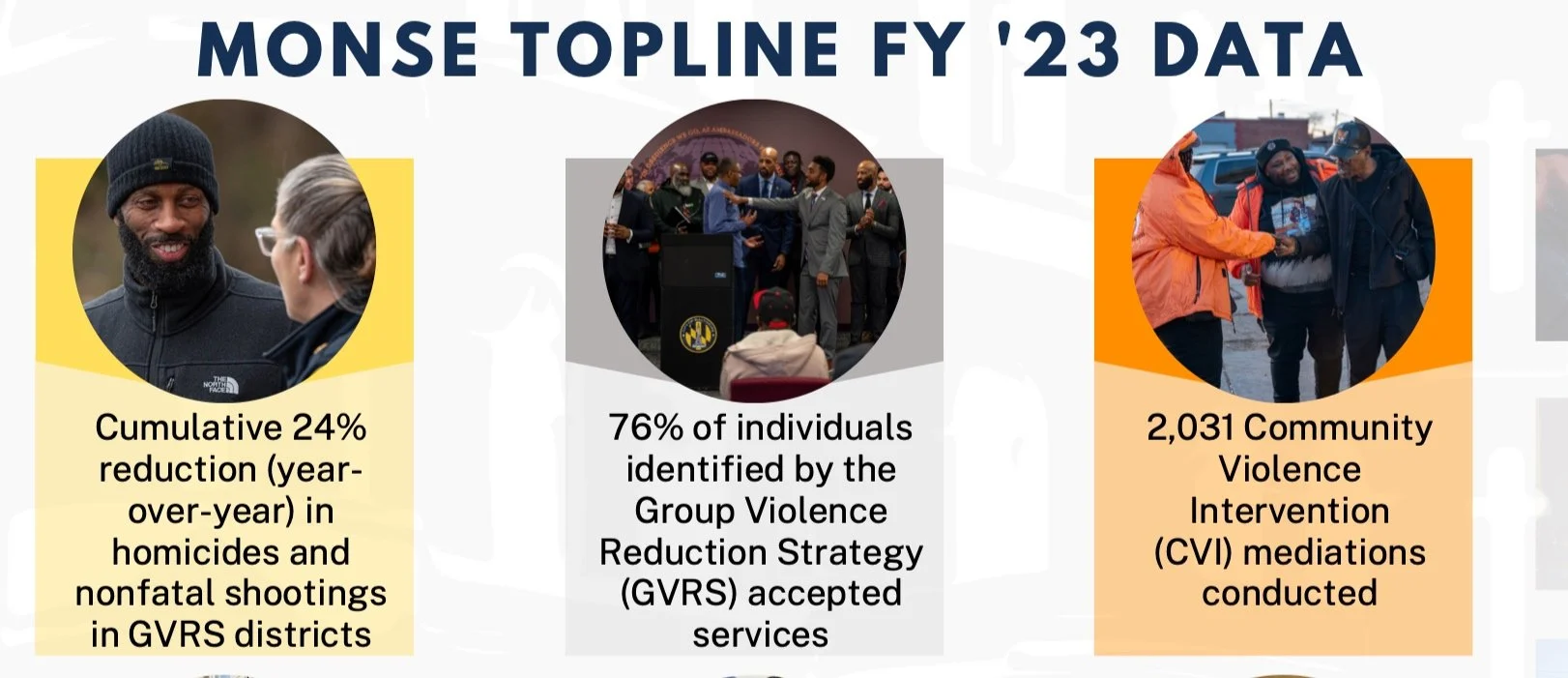

Group Violence Reduction Strategy.

One of the models utilized in Baltimore, with notable success.

In Baltimore, GVRS is housed within the Mayor’s Office—Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement—signaling that it is a priority of the administration. It also serves as a central point from which various stakeholders can come together. City-wide, public health approach.

Problem Analysis

Determine where violence is concentrated, who is most likely to shoot or be shot, and where the ‘hot spots’ are. Ensure that stakeholders agree on a common definition of the problem.

2. Intervention

Trusted community members, mothers of victims, faith leaders, social service agencies, and law enforcement all come together with community members who are most likely to shoot or be shot. It is something of an intervention.

3. Choice

Offer those at the heart of violence a choice: they must stop shooting, and if they do, they will be first in line for wrap-around services (housing, mental health, employment, etc.). If they don’t stop, they will be held accountable. Notably, providing this choice before violence is committed provides a vital opportunity for agency and going in a different direction.

Created by epidemiologist Gary Slutkin, who noted that violence moves similarly to infectious disease.

“The advantages of street outreach are clear: poor communities and especially the

criminals within them are deeply disconnected from formal sources of authority.

Outreach workers go where others cannot, trading on their status, connections, and

street knowledge to stop shootings and killings.” (Abt)

Cure Violence interrupts the spread of violence (just as you would interrupt the spread of infectious disease—by interrupting transmission).

Employs violence interrupters/credible messengers: older men with lived experience and street credibility, who are able to build relationships with those at the heart of violence.

Work independently from law enforcement, in order to maintain access and trust.

Detect and interrupt conflict

Mediate conflicts in the streets.

If an incident does occur, respond immediately in order to prevent retaliation.

Continue to monitor beef after an incident, to keep the situation cool.

Work to build trust with highest risk individuals

Identify and change thinking and behavior of ‘highest risk transmitters.’ Teach alternative responses.

Respond after incident, sending a very public message that violence is not acceptable. Build community, reclaim space.

Spread positive norms.

Check out Cure Violence’s approach.

Relentless outreach.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy—on the go.

Traditional therapy may not be practical for those at the heart of violence. Roca developed Rewire CBT, in partnership with Massachusetts General Hospital.

Effective programs utilize ‘relentless outreach.’ This means that rather than waiting for a community member to seek help voluntarily—you go to them.

Relentless outreach operates on the understanding that those most likely to shoot or be shot are less likely to voluntarily engage, as they are traditionally distrustful of authority.

Voluntary programs are likely to miss those who are most in need of intervention. Relentless outreach means showing up, texting, calling, and to continue showing up no matter what.

Such programs also operate independently of law enforcement—this is the only way to authentically build trust and work to engage those at the heart of violence.

Relapse is built into the model—understand that behavior changes takes time.

Check out Roca’s approach.

Rewire CBT is…

taught by outreach workers, not traditional therapists

facilitated on the go: on the street corner, in the car, or anywhere a young person may be

seven simple skills, 20 minutes per skill

teaches young people how to interrupt the cycle of thinking —> feeling —> doing

Participants engaged for 18 months showed a 96% improvement in behavioral health.

Roca also offers transitional employment…

They have their own work crew that contracts with the city to clean up parks, work construction, etc.

Roca understands that it takes time for a young person to develop workforce development skills. That’s why relapse is built into their employment model.

A young person is fired and re-hired an average of 4 times before completing the program. Because it is an internal work crew, Roca can support them through that process, until they are ready for a job in the community.

Hospital Intervention.

Hospitals are crucial intervention points—community members who may have been previously disconnected from support can now be reached. But the right person has to be there to reach them.

Violence Intervention Advocates are trained specifically to work with victims of community violence.

When a victim arrives in the hospital, they are immediately connected with a Violence Intervention Advocate.

While the doctors treat the physical wound, the Violence Intervention Advocate focuses on the mental and emotional repercussions of the trauma.

When the individual discharges from the hospital, the Advocate does home visits to ensure follow-up of care. (Including mental and emotional care for PTSD.)

Ensures patient’s privacy is protected. Ensures proper boundaries with law enforcement while in hospital. (Not taking property, etc.)

Advocate coordinates with Violence Interrupters to ensure continued support, and to work to prevent retaliations.

It is crucial to understand that the patient may be initially distrustful. The Advocate is there for the patient’s safety and healing, and to ensure physical, mental, and emotional care while in the hospital and after returning home.

Neighborhood Trauma Response Team.

Boston’s Community Healing Response Network is a crisis response team, arriving directly to the scene after incidents of community violence. It is housed within the Boston Public Health Commission’s Office of Violence Prevention. The City of Boston has dedicated resources and attention to violence as a public health crisis, not merely a criminal problem.

The Neighborhood Trauma Response Team does just what it sounds like—responds immediately to incidents of community violence. Their focus is on healing. They…

Connect victim, perpetrator, family members, witnesses, neighbors, and anyone who was near the incident to support for the trauma they experienced or witnessed

Respond immediately to the scene, in order to connect individuals to resources as soon as possible

Flyer around the scene, with information about resources for processing trauma, grief, and loss

Help to organize and support vigils, funerals, and memorials

Host pop-up events after the incident to reclaim the space, denounce violence, and offer support

The team has regular high visibility in neighborhood ‘hot spots,’ walking around, building relationship, and hosting community meetings

The Trauma Response Team focuses on connecting anyone who was impacted by a traumatic incident with resources to support healing, and to process trauma, grief, and loss.

Normally, after an incident of community violence, law enforcement is the main (or only) responder to the scene. The Neighborhood Trauma Response Team fills a vital gap—providing resources and support to deal with the massive trauma that the neighborhood just experienced. With a focus on healing.

Without that support, the trauma goes unchecked, unprocessed, and untreated. Boston has invested in supporting communities and neighborhoods, and treating violence as the public health crisis it is.

Prevention is a smart investment.

Investing in prevention is a tiny fraction of the cost—

and it means keeping more community members alive and out of prison.

One model, Boston Uncornered, saves taxpayers roughly $83,000/yr/individual engaging in the program.

Roca uses a Pay for Success Model.

Private investors pay 85% of the cost upfront. Roca engages young men at the heart of urban violence. When they are successful in reducing incarceration rates, they save Massachusetts millions of dollars—which the state then pays back to investors:

“At the project’s target impact of reducing incarceration by 40% the project would generate $21.8 million in budgetary savings, and at a 65% reduction the project would generate $41.5 million in gross budgetary savings.”

For every $1 invested in Safe Streets in Baltimore,

the return on investment is anywhere from $7–$19.

“If you take a gun out of someone’s hand, you

have to put something else in it.”

“Our kids are growing up being taught this is normal, and

all we have to offer them for a rebuttal is jail time. Time in a

cage with hardened criminals away from family and

society. To come home worse off than they started.”

Meeting trauma with punishment.

incarceration itself is criminogenic

…meaning that spending time in jail or prison actually increases a person’s risk of engaging in crime in the future. This may be because people learn criminal habits or develop criminal networks while incarcerated, but it may also be because of the collateral consequences that derive from even short periods of incarceration, such as loss of employment, loss of stable housing, or disruption of family ties.

Putting human beings in cages does not solve the problem.

Incarceration may actually increase crime. …high rates of imprisonment break down the social and family bonds that guide individuals away from crime, remove adults who would otherwise nurture children, deprive communities of income, reduce future income potential, and engender a deep resentment toward the legal system; as high incarceration becomes concentrated in certain neighborhoods, any potential public safety benefits are outweighed by the disruption to families and social groups that would help keep crime rates low.

Since 1975, the U.S. prison population has increased by 752%.

The United States is home to 5 percent of the world’s population,

but 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. ~Barack Obama

Black men make up 6.5% of the U.S. population,

but 40.2% of the U.S. prison population.

The United States has the highest juvenile corrections rate. It is five times higher than the next highest country.

Nationally, upon being released from correctional facilities, around 50,000 people a year go straight to homeless shelters.

In the first 8 months after community members were

18% of them lost a loved one to homicide,

23% were violently assaulted,

31% experienced a serious health incident.

The Berkshire County Jail and House of Corrections is about 30% Black.

But the population of Berkshire County is less than 4% Black.

“Money should go into the community.

That’s where the problem starts.

You gotta fix it right at the start, not wait til the end.”

Violence disproportionately impacts communities of color and low-income communities.

Striking racial gaps, rooted in a legacy of structural racism, have left generations of people of color with disproportionately less wealth and education, lower access to health care, less stable housing and differential exposure to environmental harms like air pollution. Such factors contribute to concentrated poverty, racially segregated neighborhoods and other community conditions tied to violent offending.

Violent crime increased by 19 percent within 250 feet of a newly vacant foreclosed home and that the crime rate increased the longer the property remained vacant.

Concentrated disadvantage, crime, and imprisonment appear to interact in a continually destabilizing feedback loop.

“Equal opportunities — including the opportunity to live, work, learn, play, and worship free from violence — are not afforded to all Americans and that the greatest burdens of violence are shouldered by our most marginalized and economically vulnerable neighborhoods.”

“Violent crime devastates communities already suffering under high rates of concentrated poverty.”

“In 2020…there were approximately 14 more incidents of firearm violence in the least-privileged zip codes compared to the most privileged zip codes, and almost 150 more aggravated assaults and five more homicides.”

Violence is a cycle.

Hurt people hurt people: most perpetrators of violent harm have once been a victim of violence themselves.

The vast majority of perpetrators have also been—or continue to be—victims of violence. Those who commit acts of violence often have extensive trauma histories, and have had violence committed against them.

In many cases, we see two parties with extensive trauma histories reenacting the violence of their past upon one another. We should follow the science to understand best how to intervene effectively.

“Youth who suffer from chronic exposure to violence are 32 times more likely to become chronic violent offenders.” (Bleeding Out, p. 103)

PTSD and the streets.

“In communities highly impacted by gun violence, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is more common than among veterans of the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, or Vietnam.”

Americans wounded in their own neighborhoods are not getting treatment for PTSD. They’re not even getting diagnosed.

In fact, trauma appears to have a cumulative effect. Young men with violent injuries may be more likely to develop symptoms if they have been attacked before.

More than half of urban youths exposed to violence suffer from PTSD.

How does trauma impact brain development?

In many ways:

Amygdala: the part of your brain that scans your environment for potential threats.

With PTSD, the amygdala becomes hyperactive, perceiving threats that are not really there. If you are reminded of a past trauma, the amygdala is activated, sending you into fight or flight, “survival,” mode.

Prefrontal cortex: uses reason to assess whether the perceived threat is actually a threat or not.

With PTSD, the development of the prefrontal cortex is stalled, and rationality is suppressed. Without the ability to discern a perceived threat from a real threat, the individual is sent into overdrive—reacting as if everything is a real threat. Without the ability to tell the difference from a real or perceived threat, you live in survival mode—reacting as if everything is an imminent threat.

Hippocampus: the part of your brain that stores memories.

Trauma reduces activity in the hippocampus, making it hard to discern past from present. If something reminds you of a past trauma, you may feel like the traumatic event is happening in the present moment—and react as if it is.

Violence is traumatizing. Experiencing trauma stalls brain development. The more trauma you experience, the more deeply entrenched violence becomes. Many men impacted by street violence have undiagnosed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, with symptoms including hypervigiliance, paranoia, irritability, flashbacks, insomnia, and more. PTSD may also make you quick to anger and reactivity.

Violent behavior is often a symptom of trauma. Those displaying violent behavior need effective psychological intervention. Instead, they are met with a punitive system. Punished, they become more traumatized, and violence becomes further entrenched.

Rather than effectively intervening in the cycle of violence by treating the problem itself, individuals are funneled into a punitive system, further traumatizing them, and further entrenching violence.

Individuals with PTSD often live in ‘survival’ mode. The parts of their brain that uses reason to distinguish a real threat from a perceived threat is suppressed; they feel as if they are constantly under threat—and react as such. They may be hypervigilant, paranoid, irritable, and quick to anger and reactivity.

Violent behavior is often a symptom of entrenching trauma. We must treat it as such—with therapeutic and psychological intervention. And, most importantly, with compassion—rather than punishment.

For a first—person account of living with PTSD on the streets, see ‘KIDS AT WAR.’

“A lot of us walk around with PTSD, undiagnosed,

don’t even know we have it. Because we’re taught to

suck it up, or we lived with it for so long,

it’s part of who we are.”

Violence moves like a disease.

Throughout history, whenever a new and mysterious disease appeared (AIDS, Cholera, etc.), and before anyone understood what the disease was or how it worked, those who got sick were stigmatized, and regarded as dirty. They were stigmatized and regarded as morally reprehensible. But once scientists began to understand the disease itself, and how it spread, they were able to treat it effectively—and the stigma defining those who had contracted the disease diminished. We understood that it was a disease—not a moral imperfection.

We know that violence is a cycle, with most perpetrators first being victims. We know that being a victim of violence is inherently traumatizing. And we know that trauma impacts brain development, which in turn impacts behavior. But because of how our society responds to trauma, individuals who have contracted the disease of violence are met with punishment, justice-involvement, and, often, incarceration—all of which further traumatize, more deeply entrenching violence.

The research and science around violence prevention and intervention exists. We know models that are effective. But because the stigma of violence is so deeply embedded into how we are taught to see those who are violent—from the elementary school student getting in fights at school, to the young man who is perpetrating violence in the community—the research on effective violence prevention and treatment does not, as a rule, define how we treat violence as a community.

This is a problem. The science of violence prevention and intervention is not applied in our community. Individuals who display violent behavior continue to be defined by stigma, judged and labeled, often subsuming the label of “criminal” or “felon.” There is a huge missed opportunity to apply the research, and use science to treat the disease of violence effectively.

If we were to treat this disease effectively, we would save lives, keep families together, and give young people opportunities to turn their lives around—instead of falling victim to the system.

Violence is no different. Gary Slutkin, an epidemiologist, tracked the spread of violence throughout communities that were hit the hardest by it. He found that violence spread through the community just like any other contagious disease. He argued, then, that violence could be treated just like any other contagious disease—by interrupting the spread.

The top graph tracks the spread of homicide through a town in Rwanda.

The bottom graph tracks the spread of cholera through a town in Somalia.

You will see that the spread follows the same trajectory, with an almost identical spike. This suggest suggests that homicide—violence—moves like a contagious disease. If we can track the movement, we can apply methods of interrupting the spread of contagious disease to the spread of violence. This is exactly what Slutkin did with street outreach in Cure Violence—but more on that later.

Mass shootings actually account for less than 1% of deaths by firearm in the USA, yet they dominate the media.

Young men of color from historically under-resourced neighborhoods are disproportionately impacted by homicide.

Dominant narratives perpetuate stigma and fail to humanize this crisis.

<— Check it out for a full overview of our research. We consider:

Violence as a public health crisis

Violence is a cycle (most perpetrators are also victims)

How trauma impacts the brain

The correlation between PTSD and the streets

Health disparities that make community members more susceptible to violence

The cost of homicide and incarceration vs. prevention—there is no comparison.

BERKSHIRE COUNTY, MA

In Massachusetts, 10.4% of the population,

and 12.2% of youth live in poverty.

In Berkshire County, 10.9% of the population,

and 15% of children, live in poverty.

(This increases to 32% among Hispanic children,

and to 43% for Black children.)

In Pittsfield, 13.4% of the population lives in poverty.

43.8% are described as “economically disadvantaged.”

In the Westside of Pittsfield, 42.2% of families are below the poverty line

(as compared to 5-6% of Pittsfield as a whole).

The percentage of families in the Westside of Pittsfield living below the poverty line has quadrupled over the last twenty years.

LIFE EXPECTANCY

Life expectancy is lower in neighborhoods affected by: income level, food scarcity, contamination, substance use, and stress, among other factors.

Life expectancy in Pittsfield neighborhoods:

Morningside: 71 years

Westside: 74 years

Other: 83.5 years

HOUSING

In Massachusetts, around 15,507 residents are considered homeless.

(This number has doubled since 1990.)

In Western Massachusetts, about 542 residents are considered homeless, more than double the number of 2007.

On any given night, the approximately 3,000 shelter beds are full.

There are over 420,000 children in foster care in the U.S.

3,800 of them live in Massachusetts.

325 of them live in Berkshire County.

This does not include juveniles who go missing, run away from home, or couch surf.

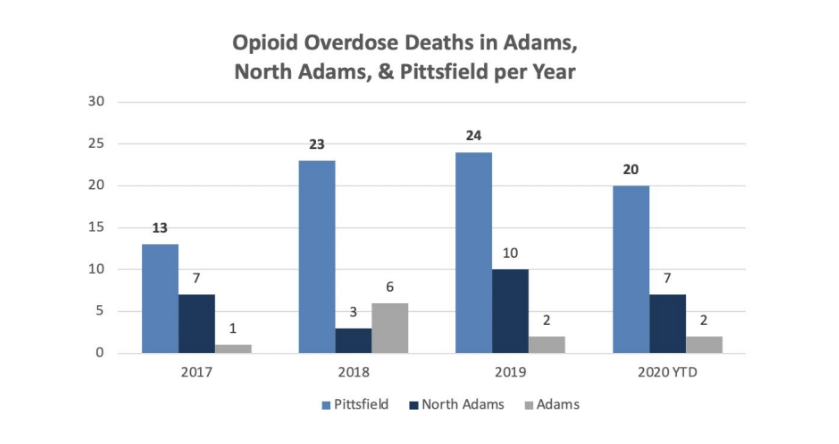

Overdoses in Pittsfield have increased

nearly 200% in the past 10 years.

MENTAL HEALTH

In 2021, around 36% of Massachusetts youth experienced at least one form of trauma, abuse, or significant stress, with almost 14% experiencing multiple traumas.

Rates of suicide in Berksire County are among the

highest in the state, at 17.4 per 100,000.

28% of Massachusetts Dept. of Mental Health clients were

arrested at some point within a 10-year period,

primarily for non-violent charges.

52% of white individuals with a mental health condition

reported receiving care, compared to

37% of Black individuals and

35% of Latino individuals.

FOOD INSECURITY

In 2021, 12% of children in Berkshire County experienced food insecurity.

Children in Massachusetts experiencing

White households: 16.2% (1 in 7)

Black households: 35.7% (1 in 3)

Latino households: 36.1% (1 in 3)

With 9.9% of the population experiencing food insecurity, Berkshire County ranks third in the state.

29% of those served by the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts are children.

Opioid overdose deaths from 2021:

Massachusetts: 32.6 per 100,000

Berkshire County: 62 per 100,000

North Adams: 71 per 100,000

Pittsfield: 88 per 100,000

(Berkshire Regional Planning Commission)

HOW DOES THIS IMPACT EDUCATION?

Children who witness violence experience higher rates of behavioral and mental health problems, challenges in school, and delayed development of cognitive skills.

Pittsfield Public Schools (‘21–’22)…

71.9% of students considered high needs.

65.5% of students considered low-income.

Pittsfield High School…

had a total graduation rate of 86.8%,

which fell to 78.6% for low-income students.

Taconic High School…

26% of the student body was officially disciplined.

79% of those students were low-income.